Before Asake, there was Small Doctor, Qdot, Zlatan, Lil Kesh, Barry Jhay, and Naira Marley, the last of which recently had his star power compared with Asake’s by online fans of both artistes. These are the kind of artistes likely to score the Headies’s Street-Hop Artiste category. You may add the infamous Portable to that list.

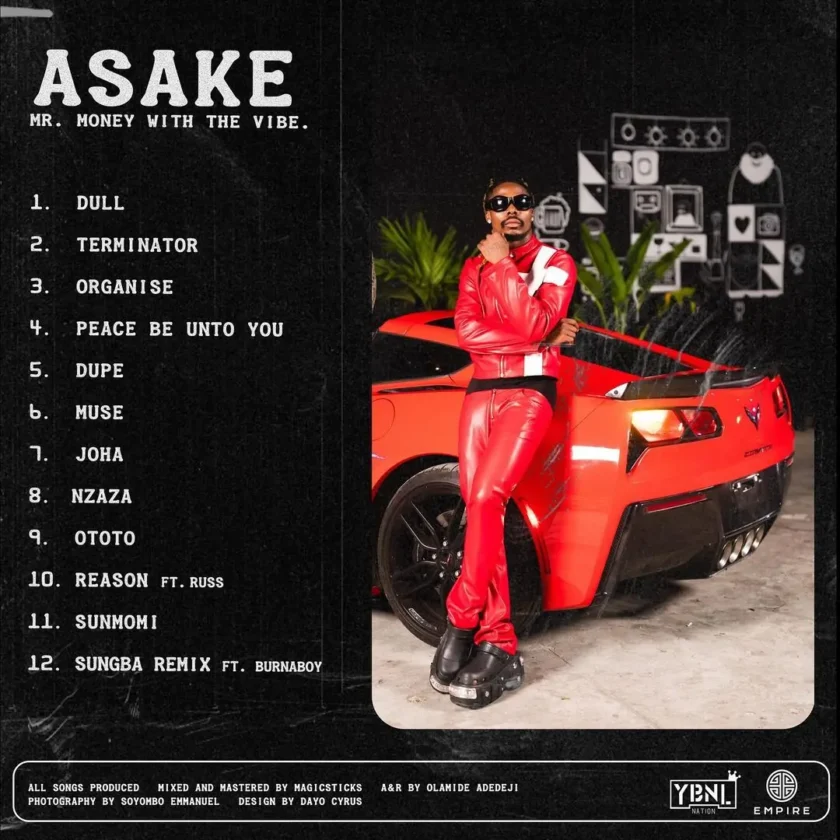

Binding these artistes is a common lingua franca—Yoruba, specifically the sort bejeweled with youthful slang. But those artistes are also bound by a fervid sense of street identity, and the kind of sound you may call niche, the kind you expect to hear at the beer shanty down your street in Lagos Mainland, but not at an uppity wedding on Lagos Island. Here’s the rub: Unlike the other artistes in that list, Asake rules both worlds. Banana Island and Badagry. Lekki and Ladilak. He proves as much with his debut 12-track album, Mr Money With The Vibe.

It is true that nowhere than in music is the messenger just as important as the message. The musician doesn’t woo ears by the quality of his music alone; but also by the quality of his public behavior. With a public profile as clean as a germaphobe’s fingernails, Asake is easy to like, especially by the kind of music listeners who judge morality in a musician as being of equal import as the music itself. Naira Marley and Portable, for instance, do not have this advantage, yoked as they are to controversy. Hence their inability to break into certain circles barred by iron doors of elitist morality. Hence Asake’s ability to do so.

It is not that Asake has a nun’s sensibilities. He also wants sex, weed, and whatnot. In Terminator, a song wrapped in South African house, he even suggests that his sexual prowess is as deadly as the cyborg character from that old Hollywood movie sharing the song’s title.

But unlike Naira Marley, Asake is subtle about his passion. In Opotoyi NM sings, “o n wo mi o, o da bi o fe do mi” (she’s looking at me; it’s like she wants to screw me). Meanwhile, Asake stashes profanity behind euphemism—it is not so sanitized that it is asexual, and it’s not so foul that it makes parents want to put cotton wool in their children’s ears.

Sometimes his euphemisms are clichéd to boot, as when he joins that long list of Nigerian male musicians who have used the banana as a proxy for the phallus. But sometimes they dazzle, as when, in Muse, he alludes to scripture in telling a lady that he can give her the appropriate level of pleasure: He sings, “make I give am unto Caesar what is Caesar’s.” It’s such a nimble subversion of that popular Bible passage, that one can forgive the blasphemy.

Asake’s uncanny decision to set almost every song in this album to an Amapiano soundscape means it was never going to be a niche album. So global is the Amapiano genre that it inspired a BBC documentary published weeks ago. Asake understands that to court an audience that goes beyond the streets, you must include in your music what is familiar to that snobbish class of music fans who are suspicious of anything from the streets. Amapiano is not only familiar, it is reliable.

As if to remind us that his heart is in the streets, Asake elides syllables as he sings English words with a Yoruba accent. It has to be deliberate, this use of basilectal English as a political statement. Just when you are about to condemn him as a bumpkin, he surprises you with a posh pronunciation of the word Ibiza. It happens in the song Muse when he promises to take a love interest to the exotic island: “My bonita, I go fly you to Ibiza”. Mere mortals pronounce the word the way it is spelled. Asake—like Anna Delvey from the Netflix series Inventing Anna—prefers its more swanky pronunciation: Eye-bee-tha. The man is Janus, with one face turned towards the bourgeois and the other to the salt of the earth.

Using choral chants, Asake appeals to both the street and boulevard at the same time. Although an uncommon technique in contemporary Nigerian pop, it is by no means Asake’s invention. A lot has been said about his Fuji strain, and truly, the man appears to have Fuji influences. The song Dupe is as didactic as many Fuji songs, and something resembling the choral chant comprises many Fuji songs. One hears such in Adewale Ayuba’s Ijo Fuji and Sikiru Ayinde’s Fuji Garbage.

In those songs, choral chants serve a democratic function. While the chants last, the songs cease to be a feat of individualism and become a communal labor. That’s what makes the vocal technique compelling—it invites the listener to lend her voice to the song. It serves that same demotic purpose in Asake’s album. But unlike his Fuji predecessors’s, Asake’s choral chants give off the air of religion. It gives you the feel of sitting in a church, only this church is in ghetto Lagos. It’s an imperfect perfection, like an angel with a sore throat.

Asake redounds to this religious experience by using many religious allusions, in his songs’ titles and verses. And in the spirit of lording over two domains, Asake’s religious excursions are syncretic. He borrows material from Christianity and Islam alike.

But as with all things sweet, too much of it induces diarrhea. There is too little variety in this album, for Asake relies on the same tricks for the most part. Perhaps this monotony is aggravated by his having one person—Magicsticks—produce all the songs. There is also the matter of his songwriting, which is mostly coherent and catchy—“before they use me, I go use my sense”—but sometimes too discursive that more than one song suffer a lack of thematic focus.

But those are minor issues. Asake mostly triumphs: He will find a home in both Oniru and Oshodi; Magodo and Mushin. Even he seems to know of his niche-bending and blending ability. In Peace Be Unto You, he calls himself a “chameleon”. No lies there.