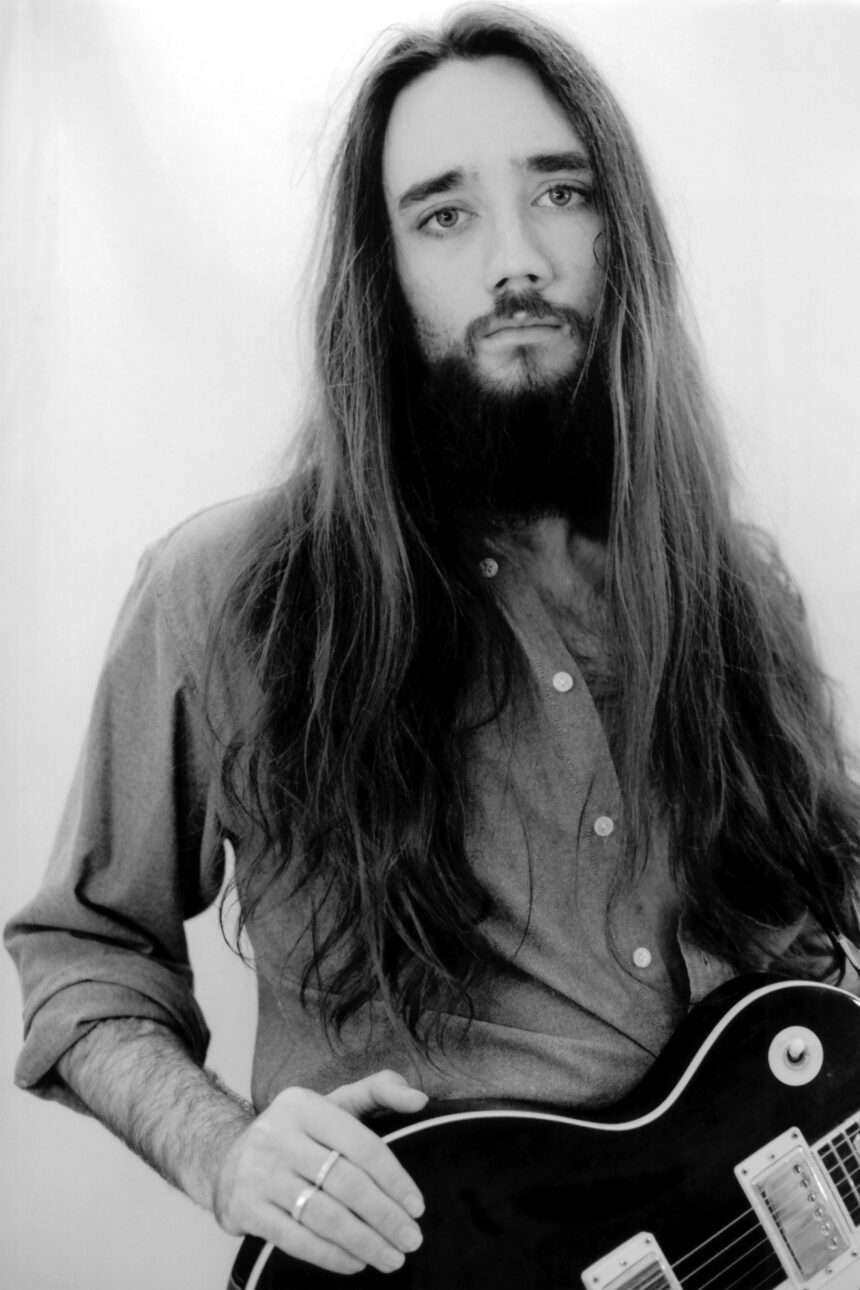

Patrick von Goble is an artist shaped by discipline, solitude, and decades of deep musical study. Working far from traditional studio spaces and industry shortcuts, he has built a creative life rooted in patience, precision, and self reliance. His latest release, Mon Obsession, was recorded entirely in his bedroom in Franklin, Kentucky, using minimal equipment and a single microphone, yet it carries a level of emotional depth and technical control that reflects a lifetime of dedication to the craft.

Known for handling every stage of his music alone, from composition and arrangement to recording and mixing, von Goble represents a rare kind of independent musician. His background spans rock, orchestral composition, and experimental approaches, influenced by both virtuosic performers and deeply expressive storytellers. Rather than chasing trends or polish, his work focuses on honesty, structure, and meaning.

In this interview, Patrick von Goble opens up about the realities of recording in imperfect spaces, the value of limitations, and the long road of musical growth. He reflects on discipline, frustration, independence, and the evolving future of music, offering thoughtful insight into what it truly means to create on one’s own terms.

Mon Obsession was recorded entirely in your bedroom in Franklin, Kentucky, without an isolation booth or studio environment. How did working in such a personal and limited space influence your creative decisions, and in what ways do you think that environment shaped the emotional character of the final recording?

I’ve spent most of my creative career working with a limited budget and even fewer resources, and this has shaped my creative process since I was in my early teens. Going all the way back to my first efforts on a Fostex X-12, I remember breaking down my composition and practicing it until it was perfect before hitting record. Overall, I think this made me a better musician. For instance, if you listen to “Tonal Liquid,” a song that is more than two decades old, you’ll hear precision in timing that is nearly mechanical—yet I did this entirely without a metronome, first laying down the drums using a single SM-57, then tracking everything else on top, and relying heavily on a digital delay pedal that left little room for timing errors. While these early recording processes were sometimes less than enjoyable, they encouraged a more disciplined musicianship. They gave me an appreciation for the old ways—for the earliest one-shot phonograph tracking methods used at the beginning of the 20th century—and for the fact that a good composer needs to be a good arranger, performer, and engineer as well if they are to work independently.

As for “Mon Obsession,” the bedroom setting in Franklin reinforced that same disciplined, introspective approach. Working in such a personal, acoustically unprepared space meant I had to be even more deliberate in every decision—the lack of an isolation booth forced me to manage bleed and room sound creatively, turning limitations into intentional texture. I had the piece structured from first note to last before I opened my DAW. This robust prior understanding allowed me to convey greater depth of feeling and meaning, as I had internalized the music on an almost molecular level. The intimacy and quiet of that small room naturally shaped the album’s emotional character: it feels close, vulnerable, and unadorned, like a private confession rather than a polished studio statement.

You have spent decades studying music across multiple instruments. At this stage of your journey, what still excites you about learning, and what aspects of music do you feel you are only just beginning to understand?

Music is a profound field. Much like the game of Go, the foundational rules are simple: so long as one picks a key, chooses chords and notes from within that key, and plays in time, one can create a song of sorts. It may not be to everyone’s liking, but a collection of notes and chords in a specific key and time signature is a song in every sense of the word. Yet the complexity of the field is boundless. Arrangement, composition, and even engineering all continue to fascinate me, and the last few generations of technical advances have opened up tremendous opportunities that would have been impossible when I was younger.

I’ve wanted to work on complex orchestral compositions since at least the aughts, when I first heard about the Vienna Symphonic Library. During my time as an endorsing composer for VSL, I’ve seen this already excellent tool improve at an astounding rate. What captures my imagination most now is the ongoing evolution of virtual players—performers with their own personalities, styles, and interpretive nuances—that will make for increasingly naturalistic and fascinating recordings. While I’ve put considerable effort into unlocking the expressive potential of these tools and exploring how they can bridge the gap between imagination and realistic orchestral realization, I am confident that innovation will allow me to do even more.

Eventually, I see music becoming vastly more sophisticated than it is today. I’m curious about future directions: not just whether AI can facilitate the performance and marketing of music, but whether it can eventually come to appreciate it. Who knows—within a few decades, someone (or something) may write the Billion Note Symphony, a work only superintelligences can truly understand. Either way, I do not doubt that music, as a profession, as a passion, and as an intellectual pursuit, will continue to evolve in interesting ways.

You handled every part of the recording process of ‘Mon Obsession’ by yourself using a single Blue microphone. What were some of the technical and emotional challenges you faced during that process, and how did overcoming them change your perspective on independent music production?

I’ve become proficient enough at sequencing that I can’t really complain about that part of the process. The real challenge lies in the tracking. Capturing a ukulele in a frequently noisy room—without an assistant and with only a single Blue microphone—presents real difficulties. The simple act of starting, stopping, and restarting the recorder is physically awkward and can easily break one’s concentration. I work to mitigate background noise as much as I can, of course, but I’d be lying if I claimed it was never a nuisance.

Emotionally, working in such total isolation (though not of the acoustic kind) means there’s no one to offer immediate feedback or share the small triumphs and setbacks. That solitude can intensify both the joy of a perfect take and the disappointment of a spoiled one. Yet, having done this for decades, I can’t claim that “Mon Obsession” required me to adjust my mindset for independent music production. In many ways, I didn’t adopt the independent mindset—I was born into it.

Overcoming these recurring challenges hasn’t fundamentally changed my perspective so much as continually reinforced it: true independence demands patience, discipline, and a willingness to embrace imperfection as part of the recording’s character. The limitations of a single microphone and an untreated room forced creative solutions—careful mic placement, strategic session timing, and acceptance of whispers of ambient sound. Far from seeing these constraints as obstacles, I’ve come to view them as essential ingredients that give independently produced music its soul.

You have mentioned that the recording process of ‘Mon Obsession’ was frustrating but ultimately worth it. Was there a specific moment during the process when you felt close to giving up, and what pushed you to keep refining the track until it reached its final form?

At this point in my career, I don’t really consider abandoning a song once I’ve started it, but peak exasperation certainly hit sometime around the 20th or 30th interruption from outside sounds that forced me to pause and restart a take. Those moments— when a distant car horn, a neighbor’s dog, or some other uncontrollable noise bled into what was shaping up to be a perfect performance—tested my patience more than anything else on the project.

What pushed me to keep going was a combination of stubborn commitment to the vision I had for the piece and the knowledge, built over decades, that these interruptions are just part of the territory when recording live instruments in suboptimal environments. I’ve learned that persistence through low points is what separates a finished work from an unfinished idea. The frustration ultimately became fuel: each spoiled take reminded me why I was doing it this way—to capture something real that sequencing alone couldn’t achieve.

My advice to younger musicians (or anyone getting started in this field) is to focus on making the physical aspects of recording as comfortable as possible. Ergonomics, a peaceful and quiet place to work, and even wearing appropriate clothing can make all the difference. If you rely purely on sequencing, as my brother, Brant (Aldus-X), does, you don’t need to worry about the process to the same extent—you may be able to hammer a song to completion while hunched over a laptop. But for those of us interested in tracking live instruments, a good physical layout is key.

Coming from a smaller town like Franklin, Kentucky, how has your environment shaped your discipline, creativity, and outlook as an artist in a global music landscape??

I write music for myself. While I hope others enjoy what I create, that isn’t the primary point—the point is to give my ideas life. Growing up in a small town in Kentucky, I didn’t sing in church or play in the school band. Instead, I worked alone. My father had a drum kit, a 12-string guitar with inadequate string spacing, a top warped by years of tension from strings that were never loosened, and a bridge that had nearly been pulled off the body by those same strings. Later on, my parents bought me an Epiphone Strat copy from Service Merchandise (a company I doubt anyone under 30 even knows existed), and I eventually got a Fender American Stratocaster. But the real prize—that which inspired me to become a musician—was my father’s record collection. Covering everything from Chick Corea to Yes to Captain Beefheart, it served as the foundation for my training, and I spent years sitting in front of the hi-fi system listening to solos, picking up the record stylus, and dropping it back down to hear them again.

I’m not going to say the process was never lonely or trying. Still, that seclusion profoundly shaped my discipline: it forced me to internalize my locus of control and rely on self-motivation rather than external validation. It fostered an introspective creativity—one rooted in personal exploration rather than collaboration or performance. And it formed my outlook as an artist: I learned to appreciate music not for fame, fortune, or attention, but for its wondrous, beautiful, and elegant nature.

As for the global music landscape today, I think technological advancements will encourage more young people to become great musicians than ever before. YouTube offers many brilliant tutorials, and Spotify provides a range of music that makes my father’s record collection seem almost trivial by comparison. At the same time, I see the algorithmic risk of people becoming boxed into a specific genre and never hearing anything outside it. I would encourage any young person who loves music to keep their ears and minds open to unfamiliar styles. Just because a genre may not be your favorite, that doesn’t mean there is nothing you can learn from it.

Independent artists often wear many hats at once. How do you manage the mental and emotional demands of being both the creator and the decision maker behind your work??

Now, you’re asking a fish about swimming. I’ve always done this, so I don’t know any other way. I have worked as a hired gun and have been a member of different bands—Knightfall being the most recent—but I am so acclimated to working alone that not having to handle all my own arrangement, tracking, mixing, and promotion is downright disconcerting.

You can manage the mental and emotional demands, but only if you become adept at switching mental modes. My advice is to avoid trying too many things at once. First compose, then arrange, then track and mix. Only after that should you worry about promotion. Remember what Henry Ford said: nothing is particularly hard if you divide it into small jobs. Working as your own record label is precisely that—a great many small jobs strung together. This sequential approach keeps the process bearable and prevents any one role from overwhelming your creative core.

Your musical influences include technically demanding artists like Jason Becker and Yngwie Malmsteen alongside expressive players like Israel Kamakawiwo’ole. How have these contrasting influences helped shape your balance between technical skill and emotional storytelling?

I’ve been influenced by so many different musicians and composers—including artists as technically demanding as Jason Becker and Yngwie Malmsteen, alongside more purely expressive players like Israel Kamakawiwo’ole—that I hesitate to pick out any single one as the dominant force. These artists all deserve credit for shaping my approach, and taken together, my expansive listening and learning from them (and many others) have taught me that there is no true line between the technical and the emotional. Five notes can be played expressively, as can fifty. The key is to understand what fits the composition.

As for the actual mechanics of a performance, controlled vibrato, use of harmonics, and even the subtle points of picking are all essential to developing an emotional palette of many colors. Obviously, extremely technical performances must be biomechanically optimized, which limits how one can pick or use a certain pattern. Still, there is no performance so complex that it needs to be devoid of emotion. These contrasting influences have shown me that virtuosic speed and precision can serve storytelling just as powerfully as simplicity and space—technique becomes a tool for richer expression rather than an end in itself.

Winning an award from the Musicians Institute of Hollywood is a significant achievement. Looking back, how did that recognition impact your confidence as an artist, and did it change the way you approached your music afterward?

I was both surprised and honored to receive the Musicianship Award. As a young person with little confidence and a limited perspective on what others could or could not do, I benefited from the award both psychologically and economically. It gave me confidence to know that my skills deserved respect not just from local music enthusiasts but also from members of the larger musical community. The Musicians Institute showed me that I could stand among the best without apology.

That early recognition had a lasting impact: it solidified my belief that rigorous, self- directed practice could yield results comparable to those of more formally trained musicians. While it didn’t fundamentally change my independent approach, it did encourage me to pursue my musical ideas with greater conviction and less self- doubt, trusting that technical proficiency and personal expression could coexist at a high level.

When you reflect on your decades of musical study and creative development, what do you feel has been the most transformative moment in your journey, either musically or personally?

The single most significant shift for me was turning my attention seriously to orchestral music around 2007 or 2008. Before that, I had listened to quite a bit of it, but my compositional roots were still firmly bound to rock. Studying the greats taught me to recognize the entire orchestra as a single instrument—with many pitches, ranges, and timbres all working in service of a unified whole. I carried this over to my later rock-infused recordings, such as “Behemoth,” which features layers of sound and a tightness of composition that would not have been possible had I continued thinking of songs as consisting of discrete parts that merely need to fit together more or less. Everything about my recent compositions flows downhill from my dissection of the classics.

Now that Mon Obsession has been out for some time and listeners have had the chance to connect with it, how has the response influenced your vision for future releases, and what directions are you most excited to explore next?

Actually, I recently released “Stellarum,” which is more traditionally orchestral than “Mon Obsession,” and I am proud of its sophistication. The listener response to “Mon Obsession” has been gratifying. It confirmed that an intimate, minimally produced recording can resonate deeply, but it hasn’t drastically altered my overall vision, as I’ve always followed my own creative instincts rather than external feedback.

That said, having completed so many highly complex recordings, I may well turn to something simpler for a while—back to my roots, if you will—if only because I believe music, while frequently a challenge, should never be a chore. I’m excited to explore that contrast: stripping things back to essentials while still retaining depth and emotional honesty. It feels like a natural evolution after pushing orchestral and technical boundaries for the better part of my adult life.

For music submission, click here