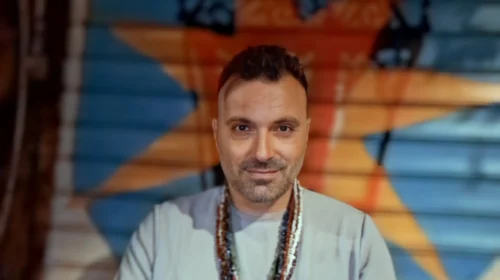

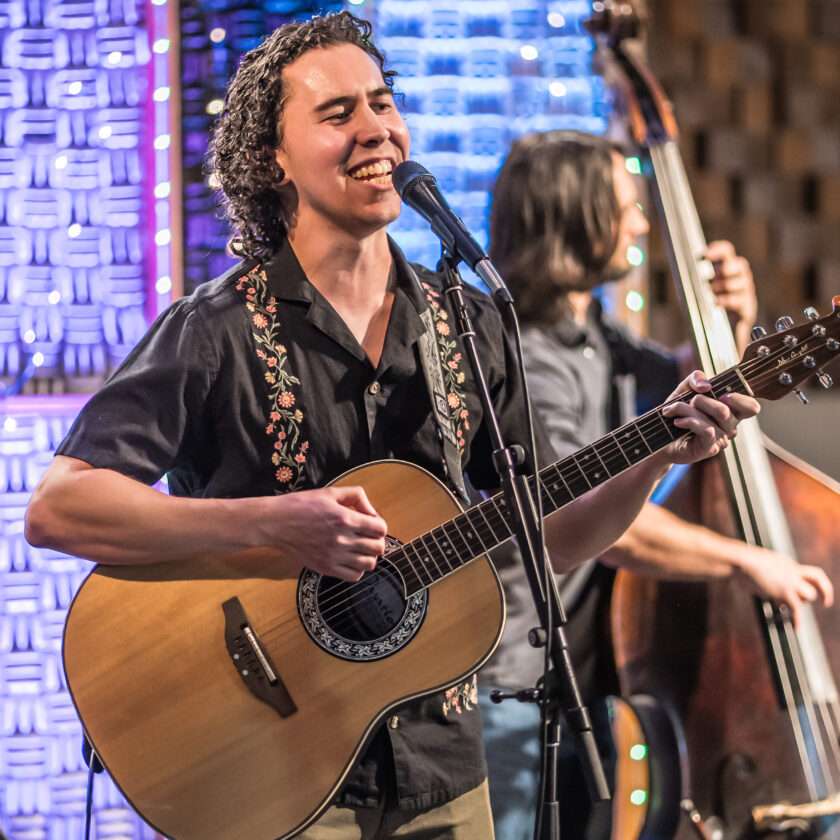

Brookhouse’s new single “Sing to Me” blends funk rock energy, jazz lounge smoothness, and unfiltered emotion into a track that feels both daring and natural. For him, the mix was not about forcing styles together but about asking what the song needed. With a live band that shifts from show to show, sometimes adding saxophone, pedal steel, trumpet, fiddle, or keys, he had already explored the song in many forms before bringing it into the studio.

At its core, “Sing to Me” wrestles with anger, judgment, and forgiveness. Brookhouse frames conflict as something that becomes performative when played out in front of others, especially online where the person with the microphone controls the narrative. The track’s courtroom imagery highlights his concern with power, polarization, and the way public discourse often trades nuance for noise.

The song is the second glimpse of his upcoming American Sounds EP, arriving in November. Where the title track reflects on the immigrant experience, “Sing to Me” focuses on political division and sham trials. Both draw on stories from his own Cuban family history while pushing into universal themes that resonate today.

Musically, Brookhouse enjoys challenging expectations. Female harmonies, dueling pianos, and playful grooves offset the heaviness of the lyrics, creating a balance that reflects his love of juxtaposition. Influences from Hozier, Frank Ocean, Santana, and John Frusciante surface in his work, but his approach remains uniquely his own.

With “Sing to Me”, Brookhouse shows that his vision for American Sounds is ambitious and unafraid to take risks. Each track builds on the last, surprising listeners while staying rooted in a deeply personal exploration of politics, power, and human connection.

“Sing to Me” blends funk rock, jazz lounge, and raw emotion—what inspired you to bring those seemingly different sounds together for this track?

I don’t usually go into a song saying, “I want to combine these unusual things together.” Instead I typically ask myself what the song needs, and this is what came out of that question.

It also helps that I perform with a rotating backing band, where not even the instrumentation is the same from show to show. I typically have a bassist, a drummer, and then an “X factor” instrumentalist. That’s been saxophone, pedal steel, keys, mandolin, fiddle, trumpet…the list goes on. So by the time I’ve recorded any of my songs, I’ve experimented with a bunch of different versions of it, and there’s this collective of 10 people that all know the song pretty well. So for each recording, I have a pretty good idea of the directions the song can take.

The lyrics touch on anger, judgment, and forgiveness—can you talk about the personal or societal experiences that shaped the story behind this song?

From what I’ve seen, any conflict between people that plays out in front of an audience becomes at least a little performative. It becomes less about nuance or empathy and more about winning. It can be in person, like on a stage, but it’s especially clear on the internet, where comment sections are often bringing out the worst in ourselves and in each other. It’s a feedback loop of hatred. And in comment sections, everyone’s on stage.

My heart breaks for the time that we spend hating each other. It’s a huge waste. We need to spend more time building, less time destroying. More time loving, less time hating.

You’ve said righteous anger can often just be self-congratulation—how does that perspective shape your approach to songwriting and performing?

Everyone thinks they’re a good person. One of the sicknesses of the modern era is how we indulge in thinking that we’re heroes, everything we do is heroic, and therefore everything we do is justified and good. It’s a symptom of the tribalism that is so rampant these days. I want to challenge that tribalism, and I think the answer is to humanize everyone.

The courtroom imagery in the second verse is striking—what drew you to frame this conflict as a trial, complete with a mic-as-gavel metaphor?

The person with the mic is the person with the power. But only for as long as they hold the mic. Once others get to share their story, the narrative can take a turn. I think it shows how the loudest voices in a room, or the people in power, sell people on their points of view – and often that leads people to be convicted without a proper trial. The person with the mic isn’t interested in due process. The whole American Sounds EP deals with this creeping sense of authoritarianism that my family experienced in Cuba.

How do you balance the heaviness of the lyrical themes with the playful, almost jam-like energy of the music?

I like juxtaposition—putting things together that you don’t see together often. It’s more fun that way.

This is your second single from the upcoming American Sounds EP. How does “Sing to Me” connect with or contrast against “American Sounds”?

They’re both political songs. but they’re very different kinds of political songs. American Sounds is about the immigrant experience, while Sing to Me is about political polarization and sham trials. At the same time, their stories are ones that people have been experiencing for hundreds of years, all around the world. They’re relevant today and they’re relevant to my family’s experiences in Cuba and in coming to the US.

Fans might notice new elements here—female harmonies, dueling pianos, a shift away from fiddle and upright bass. What guided you in experimenting with these new sounds?

These are my first two releases, and it’s so interesting seeing how people interpret them as the first two chapters of a story. But they’re not the first two songs I wrote, and they’re not the first two songs on the track list on the EP. My music is pretty eclectic, so with each new song, people are going to pick up on patterns, and then when the song after that comes out, they’re going to have to rethink those patterns. So these are new sounds to listeners of my first single, but all these elements will show up again at different points. I like to challenge people’s expectations, and that’s the only pattern that will always be true!

You’re being compared to artists like Hozier, Red Hot Chili Peppers, and King Gizzard. Do you see those influences in your own music, or are there other artists you feel more connected to?

Every song I release is going to lead to some very different comparisons. Hozier definitely helped me find my singing voice, along with Paul McCartney, Frank Ocean, Rachael Price of Lake Street Dive, Tyler Childers. Those are some of the people whose songs I’ve sung and felt very natural singing, if that makes sense. They all blazed a trail that I’ve walked for a long time now, but I’m starting to blaze my own.

As for guitar, the list is different – Santana, John Frusciante of Red Hot Chili Peppers, Mark Speer of Khruangbin, and Hozier again.

And songwriting is its own mess of influences.

At the end of the day, I just play what comes out, and it’s only later that you realize who actually influenced you to write that.

You’ve described yourself as a “political animal.” How do you see music as a way to engage with politics and society without it becoming preachy?

Hmm. What does it mean to be preachy? I think it’s when you are talking in a way like you have all the answers. But I do feel like I have some of the answers sometimes. And I really have no idea how people are going to interpret my music. So I don’t really worry about whether something feels preachy, I just write from the heart. I’m not afraid to say what I believe, and I think I have something to teach. But I also have plenty to learn. And I’m always learning new things.

Looking ahead to the full American Sounds EP in November—what should listeners expect, and how do you hope they’ll feel after experiencing the project start to finish?

Expect to be surprised. It’s a journey. Psychedelic flamenco, reggaeton rock, garage rock meets classical music played on the deck of the Titanic. It might give you whiplash. But these stories are as relevant now as they were back in Cuba as my family lived through a dictatorship that got overthrown by another.